It is no longer news that the Yoruba are famous for their greetings. As I often describe it, we greet in packages—a typical Yoruba person does not stop at one greeting. So, for example, when a Yoruba person sees you at night, the exchange might go like this:

A: Ẹ káalẹ́

B: Ẹ káalẹ́. A kú àtàárọ̀.

A: Àwa nìyẹn o. Ó dáàárọ̀ o.

B: Oo! Ó dáàárọ̀. Ká sùn láyọ̀.

A: Àmín o. Ojúure ló máa mọ́ wa.

At some point, it would almost become a friendly contest for who is the best greeter and who gets the final word.

In the same vein, the Yoruba have a preset greeting template for the beginning of a new year. We say:

A kú ọdún o. A kú ìyèdún. Ẹ̀mí á ṣe púpọ̀ ẹ̀ láyé. Ọdún á yabo.

Why do we say ọdún á yabo?

First, let us break it down. Ọdún á ya abo literally means that the year will bear the semblance of the feminine. But why is this prayer invoked for a new year?

In Yoruba, abo represents the feminine across all forms of life, including humans, animals, and plants. The Abo is known for its reproductive, fruitful, nurturing, tender, soft, ease-y energy. So, when we say ọdún á yabo, we are invoking the energy of the Divine Feminine. In essence, we are saying:

“May this year unfold for us with the softness, ease, and fruitfulness that the Feminine embodies.”

Yet, something about this invocation continues to trouble my imagination; perhaps we can decipher it together.

In the Art of Shopping Nǹkan Ọbẹ̀, a woman learns to identify obí ẹja and to avoid abo ẹran.

The female fish, whether it is panla yíyan (smoked hake) or ẹja odò (fresh catfish), is tastier, juicier, and often finer to look upon. If fortune smiles, your fish might even come packed with succulent eggs. Of course, you might even find eggs in a hen when it is slaughtered for food.

The cow, however, tells a different story.

My mother taught me to avoid the female cow. Her meat is tougher than the male’s, requiring significantly longer cooking time. In fact, you could cook it for hours without achieving tenderness. To this day, I am still unskilled at telling male cow meat apart from a female. So, I have learned to ask the ẹlẹ́ran and trust his recommendation:

“Ṣé akọ ni àbí abo?”

“Ẹ jọ̀ọ́, mi ò fẹ́ obí o.”

However, two months ago, I bought a piece of meat that stubbornly refused to soften, no matter how long I cooked it. The meat seller was my long-time customer, someone I trusted not to give me akọ ẹran. Why, then, had my meat failed me?

This culinary disappointment pushed me inwards. I began asking: why does the female cow defy the order of ease and tenderness that we associate with the feminine?

The uncomplicated answer lies in her reproductive cycle. The female cow is bred primarily for milk and calves, not for meat. These reproductive demands naturally toughen her body, making her meat a máàdáríkàn in domestic culinary.

“Máàdáríkàn” literally means do not head-butt (this one). So, it refers to an untouchable entity, something/someone that you shouldn’t dare to hurt.

On a deeper, more reflective level, however, I have been seeking to know: Does this toughness negate her feminine energy of ease? Clearly, her productivity and fruitfulness are unquestionable. Indeed, it is precisely what exempts her from being slaughtered for meat. Yet, I hesitate to frame this as purely positive or negative. I am careful about moral binaries.

I am reminded here of the words of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, as cited by Tolulope Akinwole: “Women work terribly hard in Nigeria.”

Women’s labour is expected, demanded, trivialised, and rarely acknowledged. The woman is persistently silenced, no matter what she does, with questions like, “What have you done…that is out of the ordinary?” or “What do you bring to the table?”

With this in view, let us return to the female cows’ so-called exemption from consumption. According to Hopefield, “Dairy cows endure a repetitive cycle of impregnation, birth, and milking.” While it may appear that female cows are allowed to flourish in their areas of strength—reproduction, fruitfulness, and nurturing—the reality is that this is an endlessly demanding status, one that only keeps taking without giving much in return. And so, like women’s labour, the female cow’s productivity is expected, and her exhaustion is minimised. At the end of her reproductive usefulness, she is either processed into minced meat or, in some cases, left to die.

Women are not animals. And yet, women, too, face similar relentless demands on their reproductive and nurturing capacities.

Yoruba linguistics, mirroring cosmological beliefs, associates femininity with softness, ease, care, and pampering, not because women are perceived as weak, but because it acknowledges the importance of giving women space to create, nurture, and sustain the microcosm that advances the macrocosm.

Unfortunately, this is not the average woman’s reality.

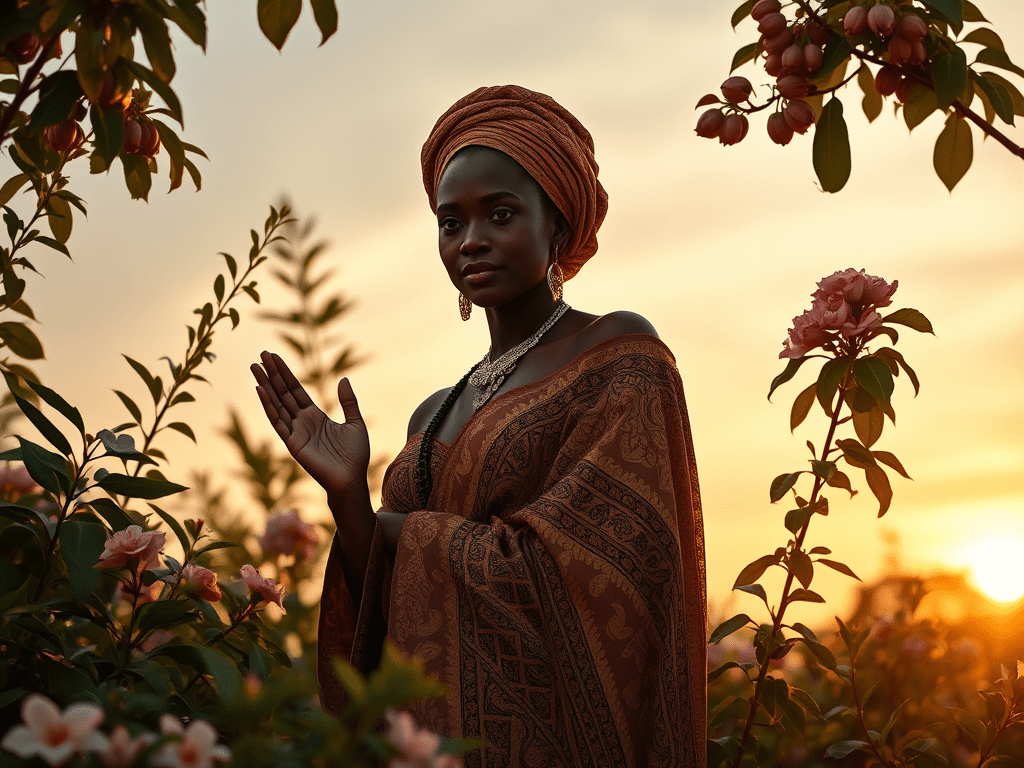

Biological reproduction already takes a physical, physiological, and psychological toll on a woman. When compounded with the rigours of daily labour, emotional labour, and social expectations, the burden multiplies. Kneading through ancient Yoruba history and mythology, it appears that women were once revered—òòṣà lobìnrin (women are deities)—portrayed as physical representations of the Divine Mother(s), worthy of sacred worship.

This brings me back to the greeting that began this reflection.

When we pray ọdún á yabo—a year of softness, ease, and fruitfulness—are we prepared to honour the conditions that allow the Feminine to embody these qualities? Or are we merely invoking the benefits of the feminine energy without recourse for the sacrifices that these demands place upon the Feminine itself?

Perhaps this is the question the greeting leaves us with.

Leave a comment