Last week, I attended the Nigerian Institute of Translators and Interpreters (NITI) Workshop by association, as I was visiting with my academic mentor, whom I affectionately refer to as “my professor.”

As one of the workshop presenters spoke about mistranslation and untranslatable words in Yoruba, we chuckled over the examples the speaker cited. For example, how do we translate “ẹ kú ilé” into English? Or how do we accurately say “ẹ kú ojú oorun” in English?

In my early days as a translator, I quickly came to understand that some Yoruba words cannot be accurately translated into English. The reason is that language is cultural. As we learned in foundational linguistics, “to learn the culture of a people, learn their language.” Culture influences linguistic content in any region. Yoruba people have a greeting for every conceivable occasion—a cultural norm that is not mirrored in English. So, English lacks the cultural framework that we convey through Yoruba greetings.

The speaker’s talk rekindled one of my pressing questions, and what better time to ask than when I was right beside my professor?

Translation & Langugage Supremacy

Tana: “Why do we translate every English word into Yoruba but insist that some Yoruba words should not be translated at all?”

My Professor: “It was not always like this. In the past, people tried to translate every Yoruba word into English. However, things began to change when they encountered these translation barriers. For example, how do you efficiently translate ẹ kú ìjókòó? What is the English for agbádá? Or why should we try to translate moi moi or akara? These are native foods. If we are not translating pizza or tacos, why do we want to translate àmàlà or ègbo?”

Indeed, translation is not just about switching a word’s form from the source language (SL) to the target language (TL). You must capture the essence of the word being translated. When Yoruba says “ẹ kú àtàárọ̀,“ the speaker acknowledges all the events that you have weathered in the course of that day—the good, bad, or exhausting. Which English word or phrase could sufficiently capture this essence?

Ironically, the Yoruba language behaves differently. Recently, I came across an Instagram post where someone corrected the error of pluralising Yoruba common nouns in English. According to the author, we should not write “Orisas” in English to indicate more than one Orisa because Yoruba has its own plural markers. This is true, and even I have struggled with the notion of writing Orisas, the Yorubas, or the agbadas.

Yet, how do we indicate plurality when writing Yoruba nouns in English? If we were to follow the author’s opinion, would we then write Olodumare sent for àwọn Orisa? This made me ask:

Which language’s rules should we defer to when we are writing? If the source language is English, should we disregard its grammar rules to conform to Yoruba’s?

A commenter on that post said that they would defer to Yoruba grammar rules and explain their rationale in a footnote.

But as a Yoruba woman and a Yoruba linguist, I find this approach flawed.

A growing Yoruba supremacy is breeding, especially on the Internet in recent times, and it is not entirely unfamiliar. When people revolt against one extreme, they often swing to the other extreme. Such is the need to place Yoruba above every other language. While Yoruba is indeed an ingenious and sophisticated language, it does not make other languages inferior.

This approach has led to another problem: our compulsion to translate every English word into Yoruba. My professor told me of a group who once translated ‘ball’ as òroǹbó àfẹsẹ̀gbá! I chortled at the creative audacity.

Like English, some words are absent in the Yoruba vocabulary because Yoruba lacks the social frameworks that necessitate those words. Take fridge, for example. The item did not initially exist in Yoruba society, yet we translated it as ẹ̀rọ amómututù (a machine that makes water cold) in Yoruba. Why did we not simply leave it as “fridge,” just as we would not translate “agbada” into English? However, here is the sweet spot: even if we choose to leave the word as it is, Yoruba grammar requires that any borrowed word obey its phonological rules. Hence, “fridge” becomes fìríìjì.

Now, this reminds me fondly of some of my Yoruba students in the U.S. during my Fulbright year. In their effort to master their Yoruba writing, they would write sentences like “Mo antisipéètì láti rí gọ́vínọ̀ lanaa.” It is technically incorrect, but their attempts show an admirable desire to internalise Yoruba’s structure.

My students are not alone in this struggle. Today, some insist we must speak “pure” Yoruba—no code-mixing, code-switching, or filler words. But language does not function that way. Language is mobile and dynamic. Contact between languages inevitably leads to the expansion of vocabulary, which includes the incorporation of loan words. Loanwords are a natural part of linguistic evolution. In other words, loanwords are a mainstay in any language. The brilliant thing language then does is to adapt borrowing to obey its grammar rules.

Yoruba demonstrates this brilliantly through language engineering—creating indigenous lexicons like ẹ̀rọ amóhùnmáwòrán (a device that transmits sounds and pictures) for television—and direct borrowing, such as glass becoming gílààsì, with the consonant cluster broken and a vowel introduced at the word ending to obey Yoruba’s phonological rules: no consonant cluster and no coda.

This explains why even proper nouns, such as the names of countries, often undergo translation, and this led to my next question.

Èṣù is not Satan!

Credit: Premium Times

Tana: “What do you think made Samuel Ajayi Crowther translate Satan as Èṣù in the Yoruba Bible? Was it just an attempt to translate every English word, or was there an ulterior motive?”

My Professor: “I cannot speak for Crowther’s motive because I was not there. However, I suspect it must have been because he needed to translate every word. Tell me, how many English words can you find in the Yoruba Bible?”

My professor was right—there are none. But I pointed out that proper nouns were loaned, not reattributed. Philistine is Fílístínì, Jesus is Jésù, angel is áńgẹ́lì. All the ethereal entities (read as angels) maintain their actual name. Why did Crowther rename Satan as Èṣù, and not Sátánì?

As my professor explained, perhaps Crowther compared their perceived traits and concluded that they were similar, hence the name attribution. But if this were the case, why were none of the angels renamed after any of the Orisa? For example, could Angel Michael not have become Ògún? Moreover, history tells us that Crowther came from an Egúngún lineage. So, how could he have mistaken Èṣù’s nature?

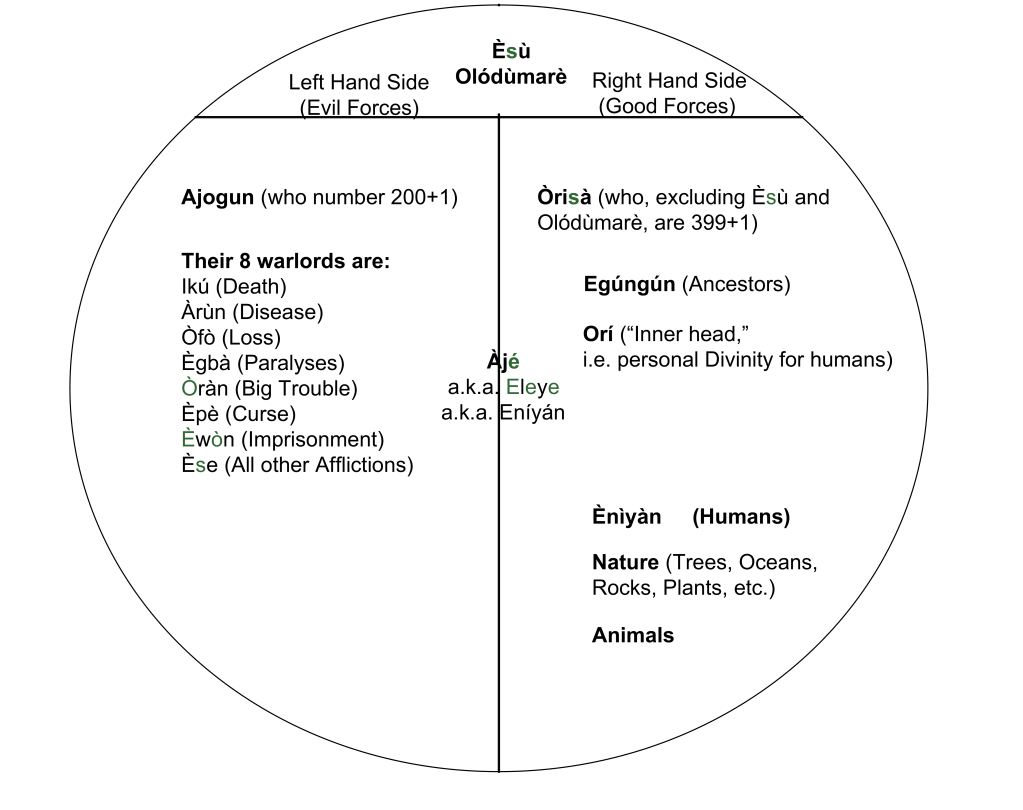

In Yoruba cosmology, Èṣù is positioned at the centre—the Ajogun (malevolent forces) are on the left, and the Òrìṣà (benevolent forces) are on the right. Èṣù and the Àjẹ́ occupy the middle, neutral status, balancing both positive and negative forces.

Credit: Spirit Intimacy

Èṣù is the Òrìṣà of justice, rewarding the upright and meting out punishment to those who err. In contrast, Satan, as portrayed in Christian theology, “goes about like a roaring lion, seeking whom to devour.” His mission is “to steal, kill, and destroy.”

There was, therefore, no reason to equate Satan with Èṣù. This mistranslation was not a linguistic error; it was ideological, and its effects still echo today.

In Conclusion…

Language is not rote. Every translation carries a worldview and showcases a people’s culture and philosophies. These intrinsic factors must be respected in translation endeavours, regardless of which language is on the receiving end.

Crowther’s translation choices, perhaps innocent in intent, unleashed centuries of spiritual confusion, where Èṣù, the custodian of balance and justice, became demonised in his own land. Our task now is not to romanticise Yoruba at the expense of other languages, but to restore balance by honouring each language within its cultural ecosystem.

Let us also remember that language is an ecosystem, and it cannot be restricted; otherwise, we risk its extinction.

Leave a comment